Economic Warfare: A Brief History

March 17, 2022

The ongoing Russia-Ukraine war and subsequent rounds of economic sanctions has highlighted the important role of money in conflicts.

Over the course of centuries, nations have utilized money as a means of control and geopolitical influence. Financial instruments and economic sanctions have been wielded like any other weapon.

In fact, President William Taft’s foreign policy became known as one of ‘Dollar Diplomacy’. President Taft explicitly referenced the interchangeability of traditional weapons and debt in his State of the Union Address in 1912, explaining that his foreign policy was to “substitute dollars for bullets”.

This article uses historical case studies across multiple centuries to demonstrate how money has been weaponized or used as a geopolitical tool in conflicts.

PILLAGING, PLUNDERING & SIEGES: MONEY’S IMPORTANCE IN CONFLICT

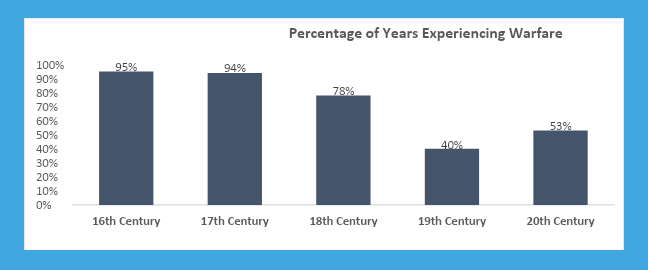

A state’s financial strength has always been an important factor in determining military outcomes, but this influence became more pronounced in 16th century Europe. Considering that 95% of the years between 1500-1599 in Europe experienced war, it is not surprising that this inflection point occurred in 16th century Europe.

However, why did money and finance become more influential for military outcomes in this period specifically? The answer lies in a group of technological innovations known as the “Military Revolution”. In particular, the introduction of gunpowder dramatically altered how armies waged war. Historians Gennaioli and Voth explain:

“The spread of cannon after 1400 meant that medieval walls could be destroyed quickly. Fortresses that had withstood year-long sieges in the Middle Ages could fall within hours. In response, Italian military engineers devised a new type of fortification — the trace italienne. It consisted of earthen bulwarks, covered by bricks, which could withstand cannon fire.

These new fortifications were immensely costly to build. The existence of numerous strongpoints meant that wars often dragged on for long periods of time – winning a battle was no longer enough to control a territory.”

In short, gunpowder facilitated the rise of cannon-warfare, which led to the existing flimsy fortresses being replaced with stronger fortifications that could endure cannon fire. Building these fortifications was expensive. However, these stronger fortresses also made battles longer since destroying enemies’ strongholds became harder to conquer.

At a higher level, new technologies like gunpowder, cannons and firearms required training soldiers on how to operate them in battle. This operational necessity slowly led to the creation of standing armies, requiring further investment from the state. Consequently, the costs of organizing and maintaining a standing army were outrageously expensive before war even began.

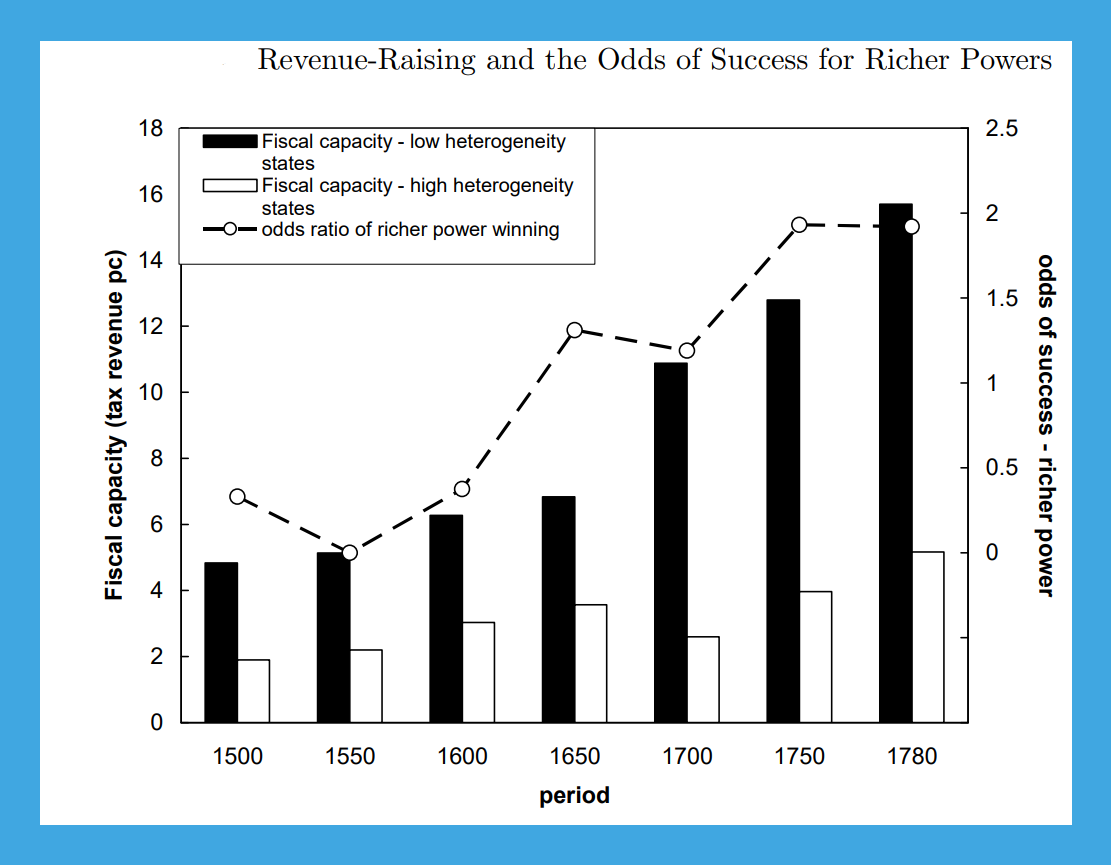

As the costs of funding militaries rose, economically powerful countries obtained a meaningful advantage. The chart below shows how much of an advantage these richer countries possessed during war over time:

COUNTERFEITING WARS

“Their principal dependence is not upon their arms, I believe, so much as upon the failure of our revenue. To think they have taken such measures, by circulating counterfeit bills, to depreciate the currency, that it cannot hold its credit longer than this campaign. But they are mistaken.” – John Adams (1777)

As money became more influential in dictating the outcome of military conflicts, warring nations quickly devised strategies for weaponizing money. An early example of this is found in Revolutionary War, when Britain attacked America’s paper currency (“continentals”) by flooding the market with counterfeit bills. The objective was to destroy this paper currency’s value by causing inflation due to an oversupply of bills. Benjamin Franklin complained:

“Paper money was in those times our universal currency. But, it being the instrument with which we combatted our enemies, they resolved to deprive us of its use by depreciating it; and the most effectual means they could contrive was to counterfeit it. The artists they employed performed so well, that immense quantities of these counterfeits, which issued from the British government in New York, were circulated among the inhabitants of all the States, before the fraud was detected.

This operated considerably in depreciating the whole mass, first, by the vast additional quantity, and next by the uncertainty in distinguishing the true from the false; and the depreciation was a loss to all and the ruin of many.”

The British circulated counterfeit bills by providing Patriot deserters and British loyalists with counterfeit bills to spend at local businesses. Britain’s counterfeiting operation became so large and successful that the penalties for counterfeiting were significantly escalated. American officials put out bounty rewards for counterfeiters, and in one case a deserter from Pennsylvania’s 8th Regiment captured with counterfeit bills was sentenced to death by George Washington.

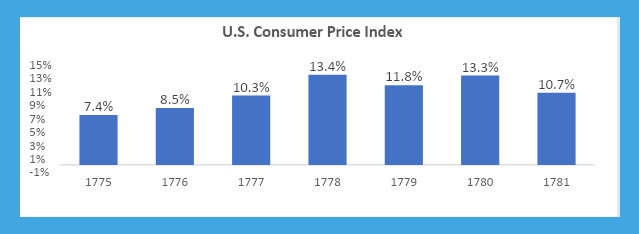

Britain’s counterfeiting successfully devalued America’s currency and provoked inflation. As shown below, the U.S. Consumer Price Index hit 13.4% in 1778 and remained above 10% from 1777 through 1781.

This currency and inflation problem really came to a head in 1781, when $225 worth of paper Continentals equaled $1 in specie. This was a dire situation, given that the average monthly salary for privates in the Continental army was just $5. Despite all the damage that Britain’s counterfeiting campaign inflicted, there was one silver lining: the innovation of inflation-indexed bonds.

To address the rampant inflation eroding soldier’s pay, Massachusetts issued inflation-indexed bonds to soldiers as a method of “deferred compensation” for their service in 1780. In order to insulate the bond payments from inflation, the values were tied to a consumer price index.

Any recent chart of the Russian ruble will prove that the concept of targeting an enemy’s currency during times of conflict is still widely practiced.

RAI STONE SANCTIONS

Turning to the current conflict, Western allies’ decision to cut off Russia’s access to foreign currency reserves was a significant punishment economically. Putin was relying upon these reserves to support the ruble when Western sanctions inevitably struck, which would cause the Russian currency to plummet. However, as Bloomberg’s Matt Levine so eloquently put it:

“‘Foreign currency reserves’ are not an objective fact; they are mostly a series of entries on lists maintained by foreign-currency issuers and intermediaries (central banks, correspondent banks, sovereign bond issuers, brokerages). If those people cross you off the list, or put an asterisk next to your entry freezing your funds, then you can’t use those funds anymore.”

This strategy of blocking access to important financial assets to strongarm an adversary is nothing new. In fact, this situation is like one that occurred on the Pacific Island of Yap. First, however, we must discuss the unique Yap currency.

The natives of Yap have used ‘rai stones’ as their currency for centuries. These ‘stones’, however, are huge limestone discs that weigh up to 8,800 lbs. and stand as high as 12 feet.

The Yap locals canoed to limestone-rich Palau Island and ‘minted’ (mined) this bizarre currency. After returning to Yap, the local Chief publicly valued each rai stone based on size and weight. Locals subsequently purchased rai stones in front of their peers so that there was a public “proof of transaction”.

While strange by modern standards in economically developed countries, this system worked for Yap. When Yap came under German administration (colonization) in the 19th century, however, the islanders’ unique currency suffered problems similar to Vladimir Putin today.

When German officials wished to improve the roads and paths on Yap, they were met with fierce resistance from locals, who refused to complete any road repairs. Yet, the Germans were unable to fine the Yap Chiefs, as any fines paid in rai stones were worthless to German citizens. The German’s solution was to “confiscate” the local’s rai stones by marking stones with a large black “X”. The Germans announced that the stones would remain confiscated until the locals finished repairing Yap’s roads.

Albeit an extreme and bizarre example, this story has clear parallels to modern economic warfare. As Matt Levine pointed out, access to financial assets like foreign currency reserves or rai stones can be restricted with a simple asterisk or black “X”. The story of Yap Island highlights that money has been weaponized as a tool for control and influence for hundreds of years.

GEOPOLITICS OF DEBT

History demonstrates that sovereign debt is often inseparable from geopolitics. For example, in their 1905 ‘Financial Manifesto’, the Russian Bolsheviks argued:

“There is only one way out – to overthrow the government, to deprive it of its last forces. It is necessary to cut the government off from the last source of its existence: financial revenue. This is necessary not only for the country’s political and economic liberation, but also, more particularly, to restore order in government finances.

We have therefore decided: To refuse to make land redemption payment and all other payments to the Treasury. In all transactions and in the payment of wages and salaries, to demand gold, and in the case of sums of less than five rubles, full weight coin. To withdraw deposits from the state savings banks and from the State Bank, and to demand payment of the entire amount in gold.

The autocracy has never enjoyed the people’s confidence and has never received any authority from the people.”

Bulgaria’s experience leading up to World War I is an informative case study on the use of debt as a geopolitical weapon.

STUCK IN THE MIDDLE: BULGARIA, EUROPEAN POWERS & DEBT

After Bulgaria achieved independence from the Ottoman Empire in 1878, the new country immediately became a financial battleground for different European alliances. For smaller and less economically stable countries like Bulgaria, securing external funding through loans from larger European powers was critical for survival. Yet, these loans were rarely straightforward financial transactions.

“From the 1890s onwards the receipt of funding was tied quite explicitly to adherence to one or other of the military blocs that were increasingly destabilizing European politics…where creditors’ and debtors’ strategic interests were aligned, one might speak as scholars of the twentieth-century Marshall Plan have done, of a form of ’empire by invitation’.”

For example, accepting a loan from Russia or France required aligning interests with the Franco-Russian alliance and all the military consequences this entailed. If the creditor country went to war, the debtor country’s destiny was tied to the war’s outcome. Should the creditor country lose, the debtor country’s fate could be dire. Therefore, countries like Bulgaria had to assess the financial aspects of foreign loans (interest rate, etc.), and the geopolitical “strings attached”.

Additionally, creditors like France, Russia, Germany, Britain and Austria-Hungary often imposed extensive controlling measures. For example, in 1902 Bulgaria accepted a modest loan from Paribas bank in Paris that contained such controls.

The excerpt below is from Paribas’ 1902 annual report:

“Jointly with the Russian State Bank, we contracted with the Prince’s Government of Bulgaria a Loan 5% gold pledged on Tobacco charges”.

In essence, Paribas was entitled to the valuable tax revenue from Bulgaria’s tobacco industry.

This foreign intrusion and subjugation to external control was unpopular in Bulgaria. Loans entitling foreign powers to any element of control were vehemently debated in parliament.

The divisiveness of these loans was best illustrated when German banks offered Bulgaria a loan with similarly intrusive control clauses in 1914. Debate in Bulgaria’s legislative house descended into violence:

“The Prime Minister, speaking in defense of the [German] Disconto loan, was struck on the head by a book hurled at him by a furious opponent.

In the melee, the parliamentary clerks were unable to keep track of who was present in the Chamber, and it was never conclusively established whether the German loan had, in fact, gained the majority Radoslavoff’s government later claimed for it.”

The Bulgarian government’s decision to accept this loan was disastrous. This financial transaction and “strings attached” required Bulgaria to align itself with Germany and the Axis Powers in World War I, which ultimately lost.

Using debt to wield geopolitical influence is still widely practiced. We have recently seen China step in to assist Russia after Western sanctions impacted Russia’s finances. Similarly, China has instituted a policy of what some call “debt trap diplomacy” in Africa, loading up nations with debt, and seizing valuable state assets when African companies inevitably default on the monstrously high debt loads provided by China.

FINAL THOUGHTS: SANCTION WARS TODAY

During a congressional testimony in 2008, then Treasury Secretary Henry M. Paulson famously stated:

“If you’ve got a bazooka, and people know you’ve got it, you may not have to take it out.”

That logic can also be applied to the use of money and economic sanctions in conflict. Trade and economic prowess can act as a meaningful deterrent for war, as countries recognize the economic consequences of starting conflict with more powerful and richer countries (or ones that are key trading partners).

This brief historical overview has highlighted how money and financial instruments are just another weapon in countries’ arsenals. Either through attacking an enemy’s currency, restricting access to valuable financial assets, and/or using debt to exert geopolitical influence, money is a tool for exercising power.

The methods and mediums through which countries wield this economic weapon changes over time, but the objectives of economic sanctions today are the same as those of centuries past: hurt the enemy by hurting their economy and restricting access to financial lifelines.

As the prevalence of “hot wars” continues to decline, economic warfare i.e. the weaponization of money and finance stands to play an increasingly key role in how wars are waged.

Sources:

*Stokes Family Office does not offer legal or tax advice. Please consult the appropriate professional regarding your individual circumstances.